Research

Learning dynamics of heterogeneous agents in N-player, m-action games.

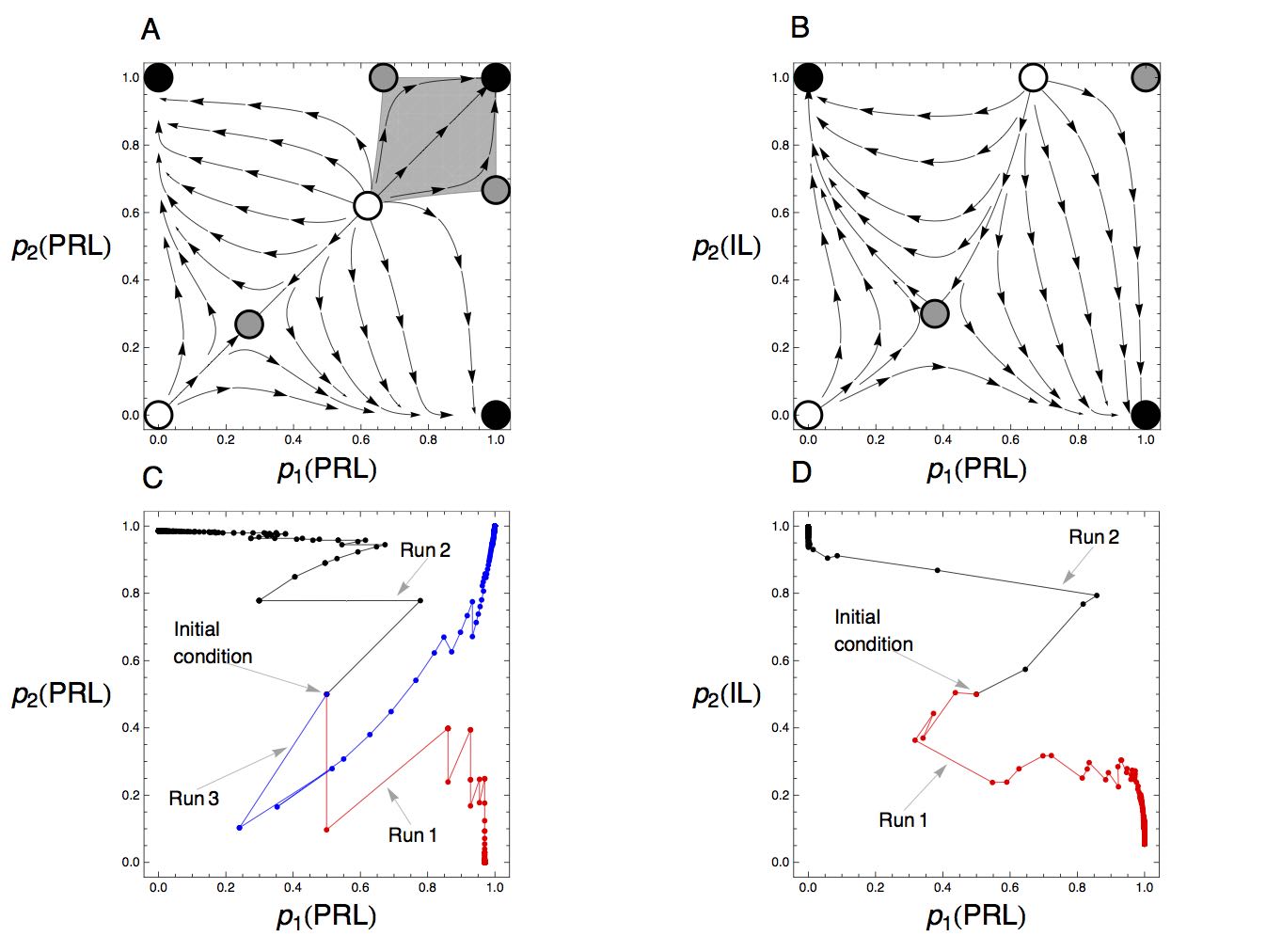

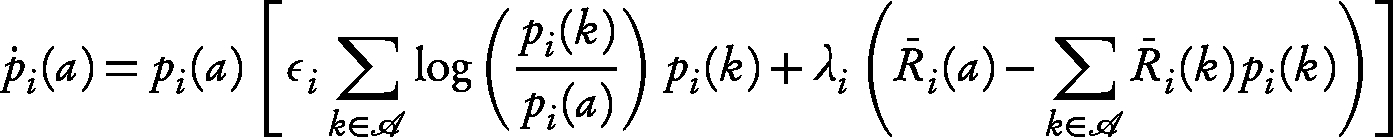

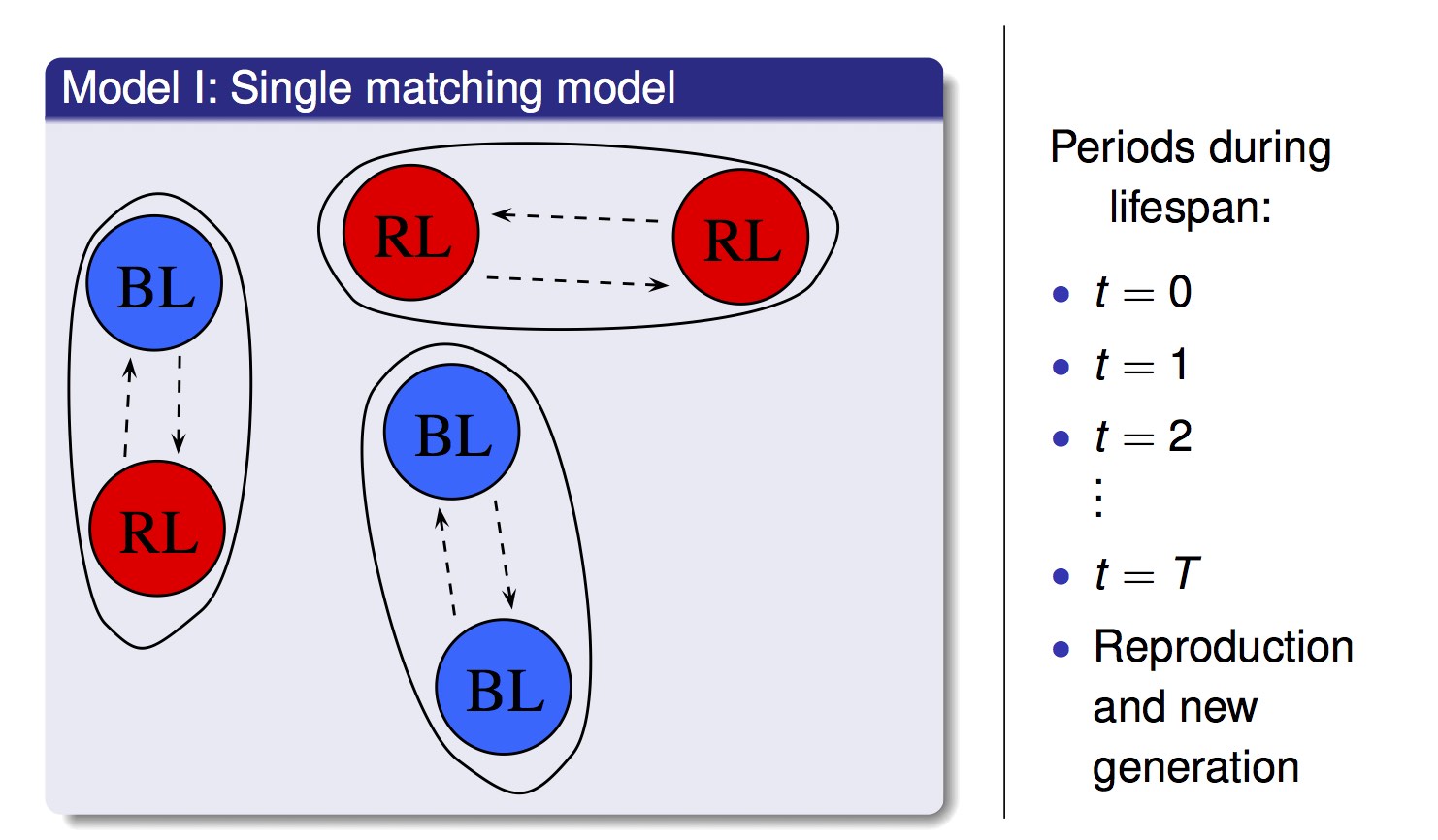

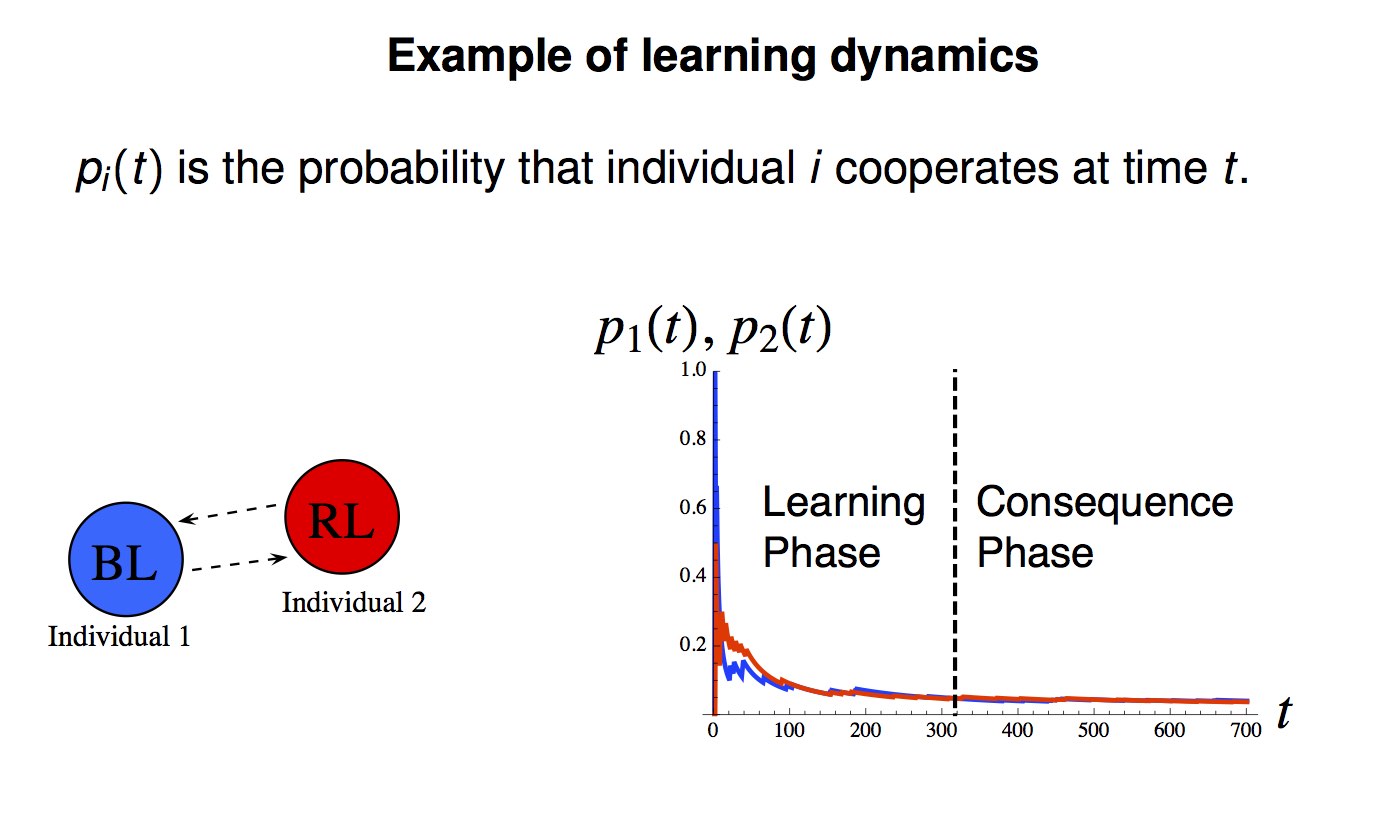

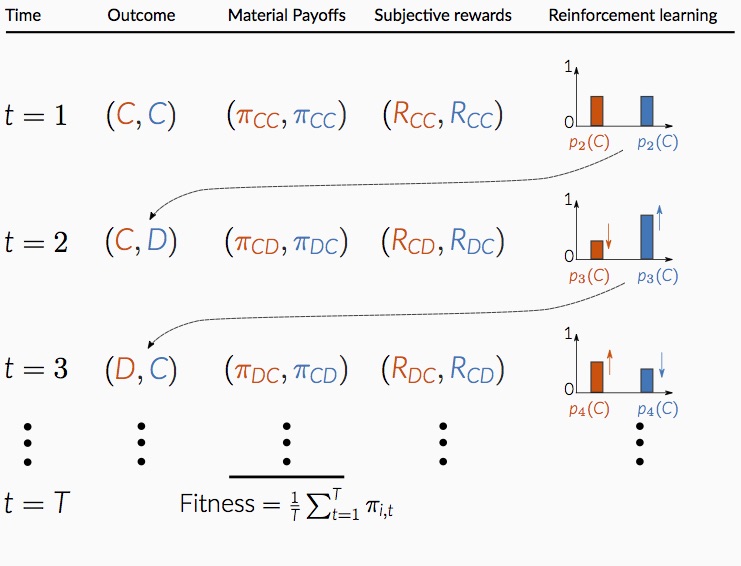

Learning is involved in virtually every behavior of humans and animals, but classical biological models of social evolution have not given full consideration to this aspect. In economics and game theory, there is a large body of research trying to model the dynamics of human learning in games. Because the learning rules used by economists do not always require a very sophisticated cognitive system, they may also apply to animal behavior. A drawback of the economists’ approach, however, is that very often it is assumed that all players in a game use the same updating rule to revise action choice. In the real world, and in order to understand invasion and competition in evolving populations, one needs to study interactions between heterogeneous agents, with possibly different learning rules and cognitive characteristics. Building on economists’ approach to learning in games, we developed (with Laurent Lehmann) a theoretical framework for predicting the behavior of agents with various cognitive characteristics interacting in iterated games with fluctuating payoff structure. The learning rules we capture span a relatively wide range of mechanisms, from simple trial-and-error reinforcement learning to stochastic fictitious play (this model is based on Camerer & Ho, 1999). We used stochastic approximation theory to demonstrate that the replicator dynamics has deeper connections to general learning dynamics than discovered before. I am working on extending the scope of the behavioral rules for which we can make equilibrium predictions, in particular considering various forms of social learning (payoff-biased imitation, conformist transmission, etc.). Another ongoing project concerns itself with the characterization of stable social states when the learning dynamics occurs in network-structured populations.

Dridi & Lehmann, 2014, Theoretical Population Biology

Evolution of cognitive sophistication for learning in games

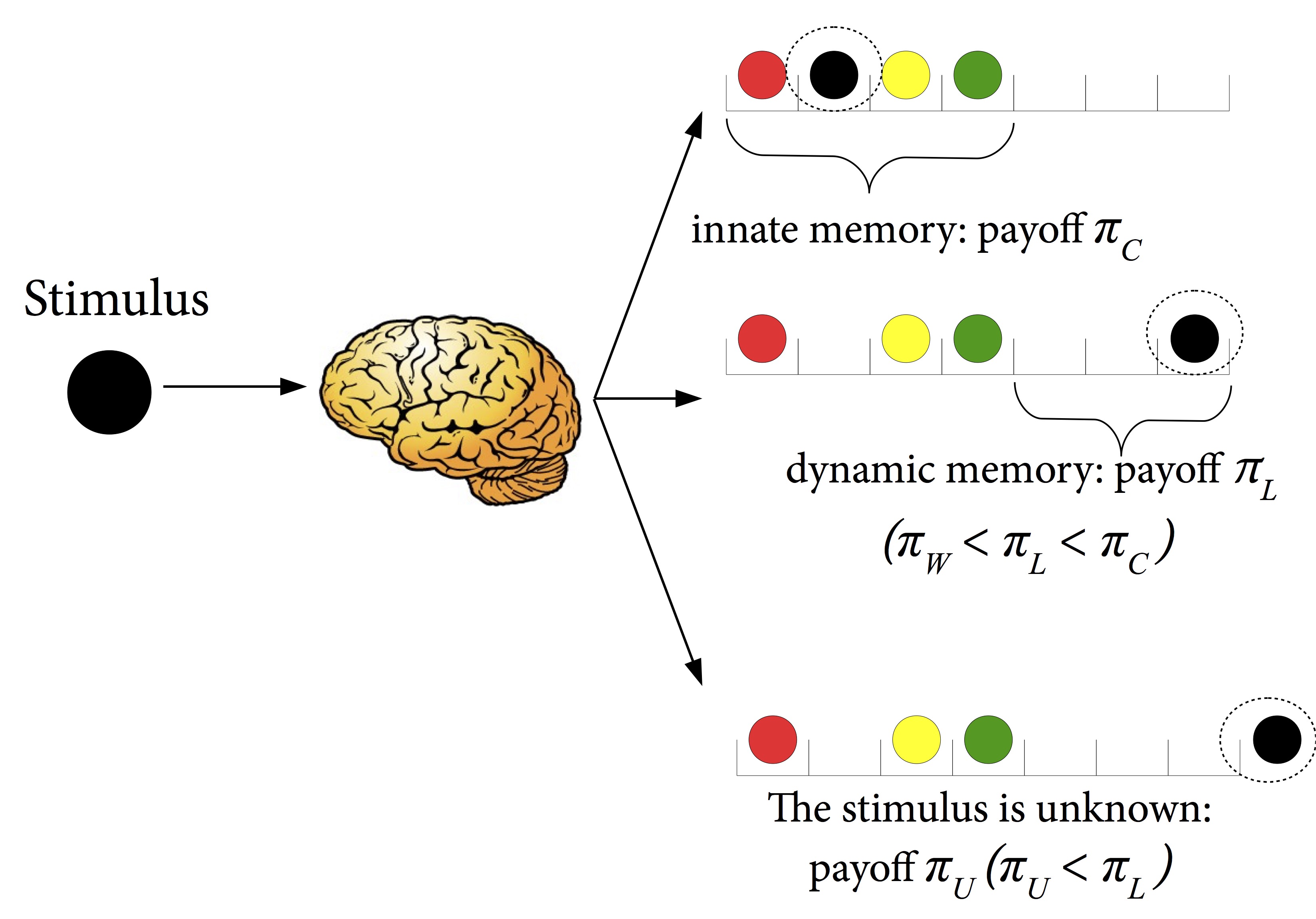

In the field of comparative cognition, researchers are generally interested in evaluating the cognitive abilities of different species. A recurrent research topic in this field is whether other animals than humans are able to form beliefs about the strategy used by social partners. This is a requirement for higher levels of cognitive sophistication, such as theory of mind. In an exhaustive article published in Animal Behaviour, we (with L. Lehmann) applied the framework mentioned above to investigate whether individuals who are able to reinforce actions without trying them out (“hypothetical reinforcement learners”) will necessarily prevail over simpler trial-and-error learners, when social interactions occur between population members. This ability to imagine non-realized payoffs can allow one to form beliefs about opponent’s behavior. We found that trial-and-error learning can be the evolutionarily stable learning rule in certain cases, in particular when the average social interaction can be described as a Prisoner’s Dilemma game, and individuals interact multiple times together (a repeated game). However, in other games (Hawk-Dove and coordination games) and when interactions were not repeated between population members, hypothetical reinforcement learning was the evolutionarily stable rule most of the time. This research thus shows that natural selection does not necessarily lead to an increase in cognitive power, even in the absence of cost for sophisticated cognition. Ongoing projects include a consideration of more cognitive types in evolutionary competition.

Dridi & Lehmann, 2014, Theoretical Population Biology

Dridi & Lehmann, 2015, Animal Behaviour

Behavioral plasticity and learning in complex environments

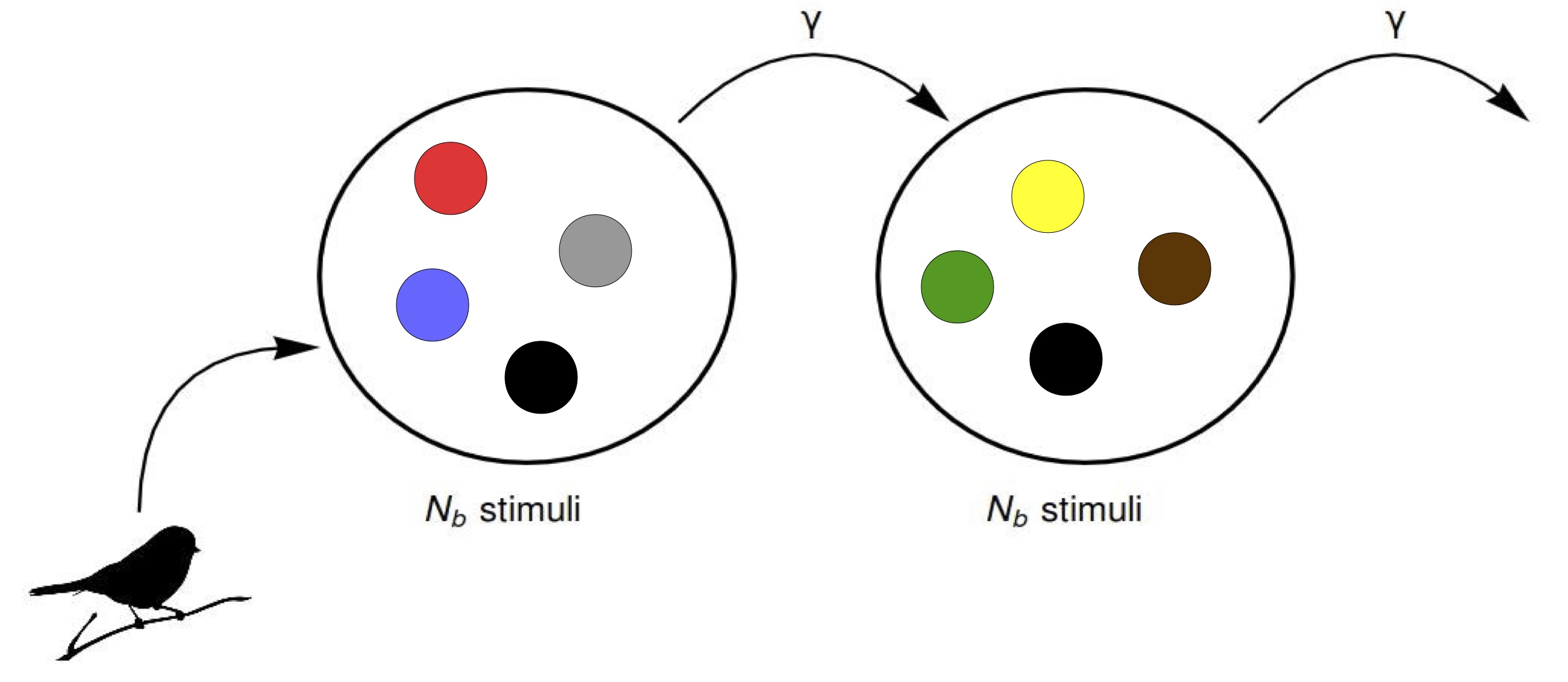

Phenotypic plasticity can take various forms, from developmental trajectories, to maternal effects, hard-wired responses to environmental stimuli (e.g., reacting to predators or preys), and learning. There has been a consensus view in evolutionary biology and behavioral ecology that learning is only useful when environmental conditions change between generations. The intuitive idea behind this “folk theorem” is that if parents and offspring do not face the same environmental challenges, then it is useless for offspring to express genetically determined actions inherited from parents. The problem with this argument is that it applies as well to other forms of plasticity (e.g., temperature in ectotherms), implying that general phenotypic plasticity evolves as well under fluctuating environments. As a consequence, environmental fluctuations constitute a necessary but not a sufficient condition for learning to evolve. We showed with Laurent Lehmann that the complexity of an animal’s environment, measured as the number of distinct stimuli encountered within its lifespan, can indeed favor learning over simpler forms of plasticity. This result occurs even in the absence of between-generation environmental fluctuations. I am currently working on extending the scope of conditions where plasticity is evolving, trying to understand its role in social frequency-dependent contexts.

Dridi & Lehmann, 2015b, Behavioral Ecology

The evolution of social preferences in reinforcement learners

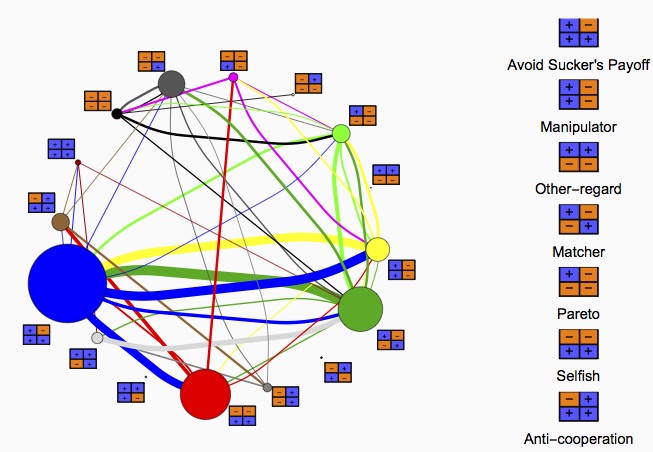

The field of the evolution of cooperation is mature and we now have a relatively detailed understanding of the conditions favoring the emergence and maintenance of cooperation in natural populations. However, a long-standing question related to this topic is that of the nature of the link between biological altruism and psychological altruism. In other words, when we observe cooperation between animals (or humans), is it because they have intrinsic other-regarding preferences? Do they generally have a tendency to prefer social outcomes that increase the welfare of others? Answering such questions requires modeling the evolution of the reward function of individuals, i.e. the function that tells which states of the world an individual finds rewarding. Neuroimaging studies found that brain regions responsible for reward processing in humans and other primates are activated when individuals merely cooperate or observe others obtaining a positive payoff. Behavioral experiments also show that humans tend to behave according to distinct behavioral types, where certain individuals seem to be pure defectors, while others reciprocate the behavior of their opponents. What is the social reward function that supports these results? In a model developed with Erol Akçay, we showed that if one lets the reward function evolve, then natural selection may lead to a range possible evolutionarily stable states. In particular, a possibility is that the population is composed of individuals having “conditional” other-regard, where individuals act in a manner similar to “reciprocators” (tit-for-tat); another evolutionary successful type is a purely selfish reward function. These results reflect to some extent the variety of human behavioral types. This project involves working with actual human behavioral data to understand how the interplay of learning and social preferences determine human cooperative behaviors.

Dridi & Akçay, 2018, The American Naturalist

Kin detection

As a psychology undergraduate, I studied the reliability of facial features as an indicator of kinship. Being able to determine whether strangers belong to the same biological family may provide fitness advantages, allowing to anticipate beneficial and/or hostile alliances. I conducted experiments asking humans to determine whether pair of photographs displaying strangers belonged to the same family. I found that the participants gave the correct answer more often than expected by chance, and the response displayed a dependence on the coefficient of relatedness between members of the pair.

This is a line of research that I am not following anymore, hence the smaller blue link to the paper below :)